feature

The Vast Untapped Market:Ocular Allergy

Many

medicated seasonal allergy sufferers would benefit from a topical ocular drop —

and they do not even know it.

BY

FRANK CELIA, CONTRIBUTING EDITOR

To be sure, these drugs are successful with good reason. They have made great strides in alleviating symptoms for millions of allergy sufferers. Nevertheless, from an ocular and quality-of-life standpoint room for improvement still remains.

This was evidenced by a study published last fall in the Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology journal, which found that a cohort of rhinitis patients being treated with systemic antihistamine and/or nasal spray reported startling increases in quality of life after a topical ocular allergy drop was added to their treatment regimen.1 The results were particularly impressive given ocular allergy symptoms were not even part of the inclusion criteria.

Add these results to the fact that many ocular allergy patients self treat with over-the-counter (OTC) products like Visine, which were designed for temporary relief rather than chronic conditions. Furthermore, the growing realization that long-term allergy induced inflammation can seriously complicate corneal surgeries such as cataract and LASIK — and we begin to perceive a vast patient population that could benefit from expert ophthalmic advice. This article explores current treatment options and trends for these too often ignored patients.

Pathology

Included in allergic conditions of the eye are seasonal and perennial allergic conjunctivitis, vernal keratoconjunctivitis (VKC), atopic keratoconjunctivitis (AKC), and drug-induced dermatoconjunctivitis. Some include giant papillary conjunctivitis (GPC) in this category as well, though strictly speaking it is not an allergic condition.

The allergic cascade, and the myriad of mediators, cell populations, and messenger molecules that interact to bring it about, are extremely complex and even after many advances of modern medicine in this area, the molecular etiology of allergic diseases and immune response mediated conditions in general are not completely understood. Research in this field is challenging because there are so many factors involved that constantly change and evolve throughout the different phases of the process, patients respond differently to environmental pathogens, and there are so many phenotypes that even accurate diagnosis becomes challenging.2

What we do know is there are four major phases to allergic conjunctivitis: sensitization; activation of mast cells, which eventually leads to their degranulation; early phase response; and late phase response.

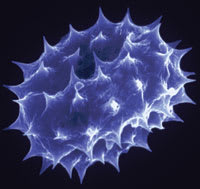

Sensitization occurs in predisposed atopic individuals when their conjunctivas are exposed to pathogens such as pollens, animal dander, dust mite fecal particles or other proteins. Directly or indirectly, these allergens encounter antigen-presenting cells (APCs), which carry antigen to naïve Th0 lymphocytes at some unknown site where a great many other interactions take place, the result is the production of immunoglobulin E (IgE), which binds to the surface of mast cells and basophils.

Thus armed by their sensitization to antigens, mast cells in the conjunctiva are ready to cause the second phase. Now when allergens in the air enter the tear film, they bind with the mast cells and mast cell degranulation begins, releasing inflammatory mediators. These include histamine, tryptase, prostaglandins and leukotrienes. This causes the patient to experience the classic symptoms of allergic disease, ocular itching, redness, chemosis, lid swelling and tearing.

The process occurs very quickly. Itching can begin just 3 minutes after exposure to the allergen. In the acute, or early, phase of the disease, the duration of the symptoms correlates with their intensity. Not all patients progress to the late phase of the disease. In fact, the vast majority does not. Late phase response occurs hours after exposure to allergens and is characterized by more persistent signs and symptoms. In this phase, eosinophils, neutrophils, basophils and T lymphocytes infiltrate the conjunctival mucosa. Late-phase patients have a more serious condition, one associated with such diseases as asthma, rhinitis, VKC and AKC, and their corneas are at risk for keratitis, limbal infiltrates and ulcers.2

Pretreatment

The first step in treatment is to find out if the patient is using OTC products, according to Francis S. Mah, M.D., an assistant professor at the University of Pittsburgh. "I would say that 75% to 95% of the patients I see with a history of allergic conjunctivitis have tried something OTC. First thing I try to do is get them off that." Such patients may have some rhinitis medicamentosa, which can confuse patient management. Dr. Mah suggests discontinuing the OTC products and starting the patient on a week or 2 of preservative-free artificial tear use, then reassessing the original symptoms at the follow-up exam.

Moreover, OTC products are less effective than the latest prescription medications. Products like Visine-A (Pfizer), Naphcon-A (Alcon) and Opcon-A (Bausch & Lomb) are safe and effective for short-term use, but because they tend to contain the preservative benzalkonium chloride (BAK) long-term use can result in corneal toxicity. Also, although these products are indicated for q.i.d. instillation, their effects only last about two hours. Thus for patients to obtain all-day relief, they must overdose, which is what often occurs.

In addition, many patients take a systemic antihistamine for seasonal allergies involving rhinitis. People often assume these drugs will have a beneficial effect on allergic conjunctivitis, but in fact the opposite may be true. The systemic antihistamines loratadine and cetirizine, which are contained in Zyrtec (cetirizine HCI, Pfizer), have been shown to reduce the volume of tear film, lowering the body's natural defense against allergens. Hence, these drugs may actually worsen ocular allergies.2

Some ophthalmologists believe discontinuing systemic antihistamines when possible is a smart idea. "It depends on what we are seeing," says Dr. Mah. "If we see a lot of puncate epithelial keratopathy and the patient is on a systemic antihistamine, as well as topical meds, I'll ask if there is significant wheezing or nasal symptoms. If it is just nasal symptoms, I'll try to get them off the systemic as well as the topical agents," adds Dr. Mah.

Many clinicians suggest a preservative-free, artificial tear regimen should be initiated immediately, even if the patient is not taking OTC drugs. In some cases artificial tears relieve the allergy symptoms entirely and no other treatment is necessary, physicians report.

Treatment Options

In general, pharmacologic treatment for allergic conjunctivitis can be split into four categories:

►antihistamines

►mast cell stabilizers

►dual action antihistamine/mast cell stabilizer combination drugs

►corticosteroids

In today's practice, few practitioners prescribe medications from the first two categories anymore. A dual-action drug is usually the first-line medication, and non-responsive patients are then switched to steroids. Patients whose insurance plans exclude coverage of dual-action drugs may be prescribed antihistamines or mast cell stabilizers for economic reasons. And some practitioners adhere to patterns set by FDA approvals. For example, Alocril (nedocromil sodium ophthalmic solution, Allergan), a mast cell stabilizer, is still the first drug of choice for VKC because that is its FDA indication.

Dual-action compounds include Patanol (olopatadine, Alcon), Zaditor (ketotifen, Novartis), Optivar (azelastine, Bausch & Lomb) and Elestat (epinastine, Allergan). These drugs are popular because the antihistamine component provides patients with rapid relief of their symptoms, and the mast cell stabilizing component treats the underlying cause of the allergic process.

Of these drugs, Patanol has been reported, in several clinical trials and comparison studies, to work better than other compounds. "It is the first drug of choice," explains William E. Berger, M.D., an allergist who practices in Mission Viejo, Calif. "It is also the only one with FDA indication for all the signs and symptoms of allergic conjunctivitis. The others are approved for itching only." However, he notes that as a specialist he treats many difficult cases and often prescribes Elestat and Optivar to patients who are nonresponsive to Patanol.

A pharmacologic reason may exist for the increased efficacy seen with Patanol. Other dual action medications appear to elicit a biphasic reaction in histamine levels. That is, the patient experiences an initial inhibition of histamine at low concentrations, but after prolonged use, at higher concentrations, the drugs actually stimulate histamine production. Alcon has presented evidence that suggests olopatadine does not elicit this biphasic reaction.3

In any case, no one is completely sure about every aspect of these drugs' mechanisms of action. Alocril, for example, has been known to relieve ocular itching in just minutes, even though as a mast cell stabilizer it is supposed to take up to 2 weeks to begin working, notes Michael B. Raizman, M.D., director of Cornea Service at the New England Eye Center. "I think the point here is we don't really understand how all these drops work. We call them mast cell stabilizers, or multi-mechanism drops, or antihistamines, or whatever, but they all have various anti-inflammatory effects that contribute to their efficacy," adds Dr. Raizman.

Another treatment option in the near future will include olopatadine 0.2%, which Alcon hopes will allow for once-a-day dosing instead of the b.i.d. requirement of olopatadine 0.1%, an improvement designed to enhance patient compliance.

If the inflammation is not overly severe, many clinicians have found success with newer, milder steroids such as Alrex (loteprednol etabonate ophthalmic suspension, Bausch & Lomb) and fluorometholone, which reduce chances of adverse side effects. Pred Forte (prednisolne acetate, Allergan) and dexamethasone are usually reserved for the more severe conditions. In these cases, some physicians will prescribe an immunomodulator such as Restasis (cyclosporine ophthalmic emulsion, Allergan) to be used concurrently with the steroid, and then continued after the steroid is tapered off in a week or two.

Patients in whom first-line drugs prove ineffective should be screened for non-compliance. "I try to educate patients about avoiding allergens, keeping hands away from eyes, not rubbing the eyes," says Dr. Raizman. "If I'm convinced they are doing everything they possibly can to avoid the allergen and the drops are still not working, then I will try a steroid, but I have to say that is certainly <5% of my patients," notes Dr. Raizman.

Speaking to patients about ocular allergies is an important first step in any treatment regimen, and springtime, when symptoms are often worst, is an opportune season to bring up the subject. You may be surprised at your patients' responses, for, as Dr. Raizman observes, "A lot of patients don't even know these drops exist."

References

1. Berger W, Abelson MB, Gomes PJ, et al. Effects of adjuvant therapy with 0.1% olopatadine hydrochloride ophthalmic solution on quality of life in patients with allergic rhinitis using systemic or nasal therapy. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2005;95:361-371.

2. Abelson MB, et al. Ocular allergic disease: mechanisms, disease sub-types, treatment. The Ocular Surface. 2003;1: 38-60.

3. Rosenwasser LJ, O'Brien T, Weyne J. Mast cell stabilization and anti-histamine effects of olopatadine ophthalmic solution: a review of pre-clinical and clinical research. Current Medical Research and Opinion.5;21:1377-1387.